Our family has some fascinating stories behind the names passed down.

My grandfather, Arthur C. Dale Sr., was likely named “Arthur” because of our English and French roots. His father, John Thomas Dale, was English, and his mother’s side carried the French heritage. There’s even a possibility that our French lineage traces back to King Louis XIV—adding a royal twist to our family story!

My uncle, Arthur C. Dale II, who passed away in 1993, shared that same noble name. His name may reflect both the legend of King Arthur and our French connection.

Their mother, Jenny Maestri Dale, also honored her side of the family in naming her children. Ferdinand was named after her father, Ferdinando; Leonard after her grandfather, Lazzaro; Chorine after a beloved cousin and childhood friend; and Maestri, of course, is the family surname.

Jenny’s roots trace back to the beautiful town of Lucca, Italy, and a small mountain village called Campi, Albareto, near Borgo Val di Taro in northern Italy.

Lucca is especially known for being the home of the “Maestri Comacini,” ancient stone masons famous for building stunning Gothic churches during the Renaissance. Many believe they originally came from the Lake Como area and were descendants of Roman architects.

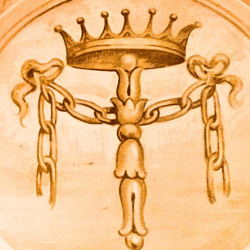

The name “Arthur” takes on an even deeper meaning when we look at a fascinating place in Tuscany: the Rotonda at Montesiepi, a round church near Siena. Inside is a real-life “sword in the stone,” just like the legend of King Arthur.

The sword was placed there by Saint Galgano Guidotti, a 12th-century knight who gave up his worldly life to become a hermit. According to legend, after a vision, he pushed his sword into a stone to show his dedication to a new, spiritual path. The chapel built around the sword became his final resting place.

The Rotonda was built in the 1100s in a style linked to the Maestri Comacini—the same group our Italian ancestors belonged to. This round church is known for its Romanesque architecture and has become a famous historical and religious site.

What’s especially fascinating is that many scholars believe the legend of King Arthur and the sword in the stone may have actually been inspired by this very story of Saint Galgano and the Rotonda.

And then, just when the story seems complete, another piece of the puzzle appears—this time in the city of Modena. In the town’s main square stands a magnificent cathedral, one of the oldest and most beautiful in Italy.

Modena, like Lucca and Borgo Val di Taro, is part of the same northern region where the Maestri Comacini once lived and worked.

Historical records show that the Maestri Comacini—family groups of stonemasons from the Lake Como region—were in charge of many major construction projects across central and northern Italy between the 12th and 14th centuries. They worked on the Modena Cathedral from the late 1100s into the early 1300s.

But the most incredible detail is hidden in the stone itself. On one of the cathedral’s arches, in the keystone, is a carved scene: Mardoc holding Queen Guinevere prisoner in a castle, while knights rush to her rescue. Among them, the names appear—King Arthur and Galvagino. It’s a direct reference to the Arthurian legends and the Knights of the Round Table.

Here’s the astonishing part: the Modena portal was created around 1120—twenty years before the first known written account of the King Arthur legend in 1136. That means this legendary tale may have been passed down through families and stone carvings long before it ever reached the page.

In other words, our family’s Italian roots may connect to the origin of one of the most legendary stories in Western history—and this is why Jenny Maestri Dale chose to name her oldest son Arthur.

If the Maestri Comacini passed down this story through generations, it’s possible we are part of that long line of storytellers, craftsmen, and keepers of legend.

There’s yet another thread connecting all these places and stories—the ancient road known as the Via Francigena.

The Via Francigena was a major pilgrimage route stretching from Canterbury, England, all the way to Rome. It passed through many of the cities and regions tied to our family’s history—Lucca, Siena, Borgo Val di Taro, and Modena—creating a living pathway through which people, ideas, stories, and faith traveled for centuries.

During the time of the Crusades, the road was crowded with pilgrims, knights, and monks journeying to holy sites. Later, during the Renaissance, this same route became a vital corridor for trade, culture, and construction—and the Maestri Comacini often followed it as they moved from town to town working on cathedrals and buildings. It’s very possible that our ancestors walked this road, tools in hand, carving beauty and legend into stone along the way.

The Via Francigena wasn’t just a physical route—it was a connection between cultures, stories, and generations. And in many ways, our family’s story follows that same path: winding through time, built on faith, creativity, and a sense of wonder.

So when we hear the name “Arthur” in our family, we’re not just hearing a name. We’re hearing echoes of English nobility, French royalty, and deep Italian craftsmanship. We’re hearing legends carved in stone centuries before they were ever written down. We’re hearing stories passed from one generation to the next, wrapped in mystery, honor, and imagination.

“Arthur” in our family isn’t just a name—it’s a legacy. And what a beautiful one it is.

Visual Journey: The Rotonda at Montesiepi

To help you visualize this remarkable place, here are some images of the Rotonda at Montesiepi and the sword embedded in the stone:

For more detailed information, you can visit the following resources:

- Atlas Obscura: The Sword in the Stone at Montesiepi Chapel

- Love from Tuscany: Montesiepi Chapel

- Wikipedia: Chapelle San Galgano de Montesiepi

Interactive Map of the Via Francigena

To explore the Via Francigena and trace the path our ancestors may have walked, you can use the official interactive map here: (viefrancigene.org).

This map allows you to visualize the route from Canterbury to Rome, highlighting key towns and stages along the way. It’s a fascinating tool to connect with the journey of pilgrims and craftsmen who traveled this historic path.